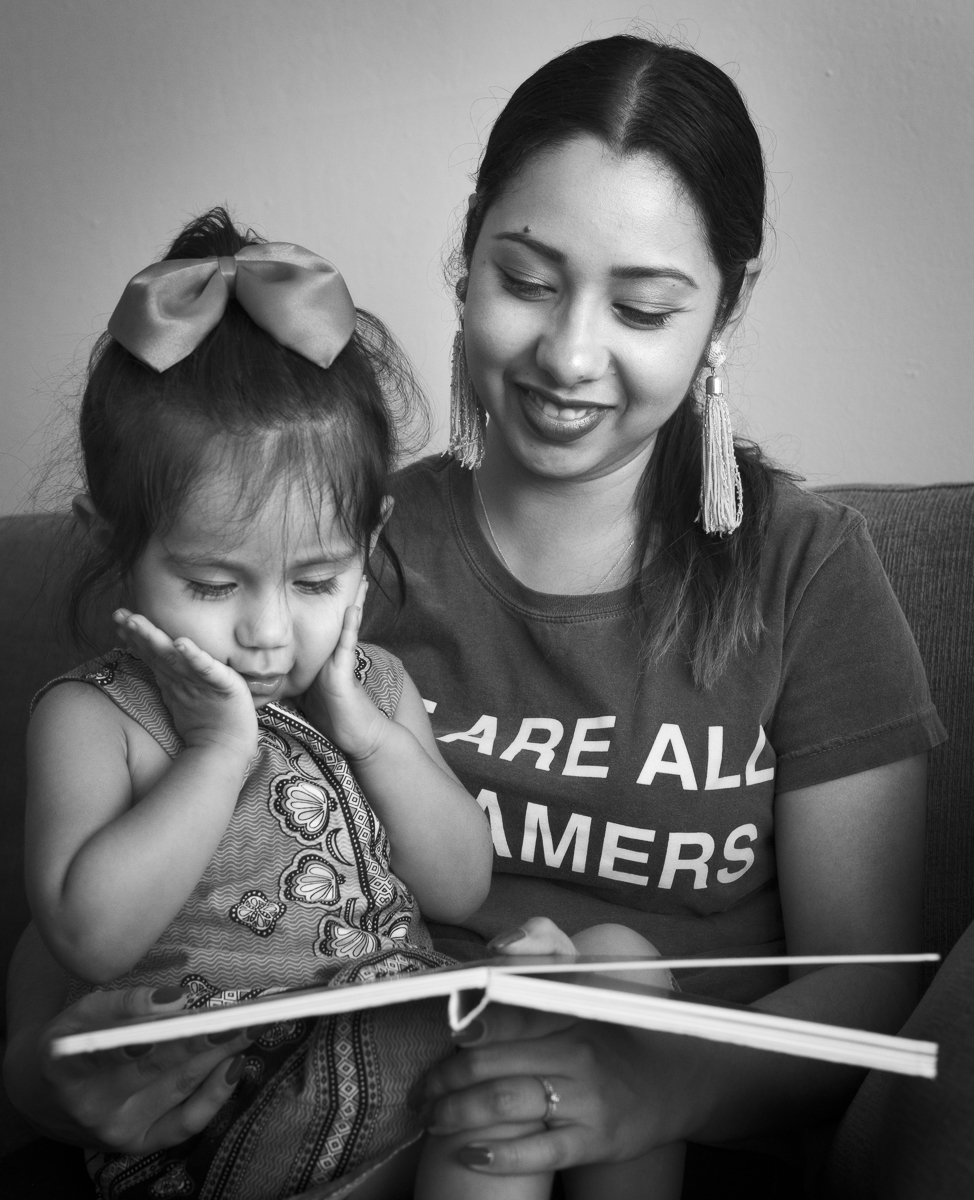

Sarahi Salamanca

Mexico

Founder of Dreamer’s Roadmap

My Name is Sarahi Espinoza Salamanca. I am 28 years old.

I was born in Lazaro Cardenas, Michoacán, Mexico. I came to the US when I was four years old. The majority of my siblings were already here. My brother and I were pretty young, so I think it worked out for all of us to just make the move now before I started school.

It didn’t really hit me to want to “adjust” to being in the States until my senior year of high school, when I found out what it meant to be undocumented in this country. Because prior to that, I was just in school all the time. I was involved in everything in school, I was in the theater, so my life was normal up to that point.

My senior year of high school, as I was preparing to apply for college and financial aid, I found out that I didn’t have a Social Security Number. Therefore, that application couldn’t be processed and I was denied FAFSA. I remember going to my counselor and telling her my situation. I told her I really wanted to go to school, that I worked so hard to get my grades and to be involved in all sorts of leadership roles on campus. But she responded, “Well, unfortunately, people like you don’t go to college and there’s no money for people like you to go to college.” I felt so horrible having worked so hard to be told, “Thank you for working hard, but it doesn’t matter because you don’t qualify for anything and high school is all the way you can go.”

That was really difficult to digest, and this was the first time that anyone differentiated me from a normal American kid going to school. I always knew I was an immigrant, but I never knew the consequences of what it meant to be an undocumented immigrant trying to go to college. At home, nobody could really tell me what I was getting myself into because nobody ever got that far in their education.

I graduated high school in 2008, long before DACA. There wasn’t a dreamer movement yet where a lot of people came forward and expressed that they’re undocumented. I think my counselor wasn’t educated on the resources for students like myself and it was very discouraging. After that, I thought that I was the only one that was going through this. But little did I know that there are about 65,000 students a year in the United States that are going through the same thing.

Then it sunk in how many other counselors were like mine, telling these students they couldn’t go to college — and how much potential are we losing as a country by not giving these kids the opportunity to get educated in the only place that they know of as home. The majority of DACA students have been here since they were very young, so this is the only place that they know as their home.

After high school, I was kind of going through a rollercoaster of emotions. I fell into depression, it got to the point where I had suicidal thoughts. It got really bad. Because you just kind of pivot into this hole where you just see no light. It’s just people constantly telling you like you don’t belong. Not even so much just with education, but then after realizing what it really means to be undocumented you can’t get a normal job like everybody else. You can’t go to the DMV and get a driver’s license. You can’t apply to healthcare like everyone else. So, there are all these other barriers that just kind of like all came at me when I was 17 years old, and without my parents. It was just a really, really difficult dark moment for me.

When I graduated high school, I moved to the Bay Area with my sister because I couldn’t really take the pressure of Los Angeles anymore. All my friends were heading off to college and I had no idea what was next for me, so I just left. I ran away from the whole problem and came to the SF Bay Area. It wasn’t until I got here that somebody from my church told me that I could go to college, that I qualified for AB 540 and there were private funders or organizations like the Bay Area Gardeners Foundation. She took me to their gala event that same year in 2008 and I was just blown away.

My mom and my dad had been in Mexico since I was 16 years old. My parents went back with the impression of coming back in six months with a Green Card and that never happened. So I graduated high school and they weren’t here. Even though I did get to go to college in 2008 with all financial support I found, I dropped out a year and a half later because my father got diagnosed with cancer. I worked full time and I sent him money. I had to work all the time to sustain myself.

DACA was kind of like a funny thing because my father passed away in 2011 — just a year shy from DACA — and I was still undocumented to that point. So, when DACA passed, I felt mad because I wished this would have come out a year ago and I could have gone to see my dad and been with him and my mother.

Then, DACA passed in June 2012. I actually remember the day; it was June 15, 2012. I was a nanny at that point. One of my friends sent me a link to it, and told me Obama had signed an executive action on something called DACA. I started reading about it and my first reaction was fear. I even told my friend not to apply that this was just a trap.

I got married in 2012 and my in-laws were the ones who kind of pushed me to apply. I didn’t want to because I knew nothing and no one in Mexico. They told me it was a once in a lifetime opportunity. They said “I know that you’re afraid, but if you do this you will have a Social Security numberor you can drive without fear. You’re going to be able to travel if something like what happened to your dad happens to your mom or another relative.

Putting things into perspective, I came to the conclusion that I would apply. Despite the fact that I was literally giving the government the information they needed to come pick me up from my house and deport me, I didn’t want to go through what I went through with my dad again.

I finally applied for DACA in October and by January, I had my DACA.

And then, I went back to school to Cañada College. DACA encouraged me to have a purpose, a reason to go to college. And when I graduated, I could actually use my degree to my advantage. When I was undocumented, even if I got that degree, I had no idea how I was going to be able to be employed.

DACA gave me the confidence to put myself out there to get a real job. My first job after having DACA was with the Girl Scouts of Northern California, which was super exciting. I actually saw the post on campus. I was at the career center like all the time and they were looking for community organizers and program instructors. When I applied for the job, I got it and I became actually both. I became a community organizer and a program instructor.

I love to teach. That’s one of my passions. I’ve always taught at church since I was 12 years old. So part of my job was to be an Environmental Science and Technology Instructor for girl scouts and it gave me the opportunity to go to neighborhoods like mine where I grew up, and teach little girls about STEM. That was super impactful for me because I didn’t even know what STEM was until I was in college. And I’m like, “Man, I think if I would have known when I was a little kid that I could be an engineer and that it was fun and circuits and electricity, I would have totally gone the engineer route.” For me, it was a very gratifying job. I didn’t even consider it a job. It was fun for me to go out to the community and teach these little kids of STEM.

I think in a nutshell, DACA changed my life because it gave me the opportunity to learn things about myself that I didn’t. It gave me the opportunity to grow in the things that I already loved and was passionate about, and it gave me the confidence to go back to school and pursue my higher education as I never had before.

I was invited by the White House to be honored as a Champion of Change by the Obama Administration for the work that I was doing with the Girl Scouts and on a blog called Sarahi.tv where I would post scholarship opportunities for undocumented students and low income students in my community. I’m currently the founder and CEO of a mobile app called Dreamer’s Roadmap. It’s a free mobile app designed to help undocumented students across the country find scholarships to go to college.

I wanted to interview people who had similar stories to ours — people who had come from low income or undocumented backgrounds and went through college to empower youth. I believe in empowering youth, in showing them that it is possible to get to college and it is possible to be successful. And if we were to expose them to the people that had already gone through it, I thought that would be impactful. But we were just doing scholarships at that point.

I have gotten several honors, which is really surreal. I didn’t really get into this work to receive honors or to receive awards. I really wanted to do this work to change the lives of other people and not feel what I went through. I feel very privileged and honored that people are recognizing my work. So much more than the certificates that I hang on my wall, I feel that these honors bring recognition and publicity and it helps push the story out. So that makes me happy. And obviously, it makes my family very proud.

DACA has been in a limbo since the Trump administration came into office. It was rescinded in September of 2017. In January 2018, it was brought back but not back in its entirety. We no longer have privileges to use Advanced Parole. New applicants that qualify for the program can no longer apply. There was a very short window when they were receiving new applications, but that was taken away very quickly. So right now, the only people that could renew are people who currently have DACA. They can only use their work permit, work authorization, and their safety from deportation.

If you don’t have DACA, or if you’re not a parent or a family member of a DACA recipient, you have no idea how difficult it was to apply for it. There were so many requirements. You cannot have even a speck of anything bad on your record. You have to present records that you were here, that you were a good person, that you were a law-abiding citizen, that you were a good student, that you are currently in college or doing work. I feel like a lot of people assume it was just one application when in reality it was several applications. There were a lot of hours of doing research on my own life — calling doctors, teachers, and calling school districts — to prove to the government that I am a good person and I need to qualify for DACA.

In this context, I think it’s important is to not use the word “illegal” to label people. Yes, a lot of people do come into this country with unauthorized entry, and that’s why people use that word, but they shouldn’t. Something is illegal, a person is not. A person is undocumented

The second thing would be for them to think about their own immigration stories and to remember that everyone in this country, if you’re not Native American, you were also an immigrant somewhere down the line. People tend to forget that, especially, the very conservative people. Maybe you were born here, but your ancestors fled their country for the same reasons my parents fled theirs twenty years ago. It just so happens that yours fled 100 years ago, but it’s the same story. Everybody’s coming to this country with a dream of a better life with a new opportunities that their current country couldn’t give them.

I tell people to remember that. However hard it is for you to look at me and label me and tell me that I don’t belong, that I’m an immigrant, that I should go back home, remember your great grandparents or your ancestor’s story. Ask your parents. Try to figure out why they left their country and I’m pretty sure that you’re going to have and you’re going to find a lot of resemblance to my parents’ story and why we came to this country.